by: Sarah Sharman, PhD

Illustrated by: Cathleen Shaw

James Lawlor was just over a year old when his parents found out that he had a rare disease called cystic fibrosis (CF). Cystic fibrosis is a chronic genetic disorder primarily affecting the lungs and digestive system. There are close to 40,000 children and adults living with CF in the United States today and 90,000 worldwide. Advancements in medical care have significantly improved the life expectancy and quality of life for individuals with CF, but it remains a severe and chronic condition.

At the time of James’s diagnosis, the underlying cause of the disease was just being discovered. Thanks to DNA mapping technology in 1989, scientists identified the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) gene and its protein product as the cause of CF.

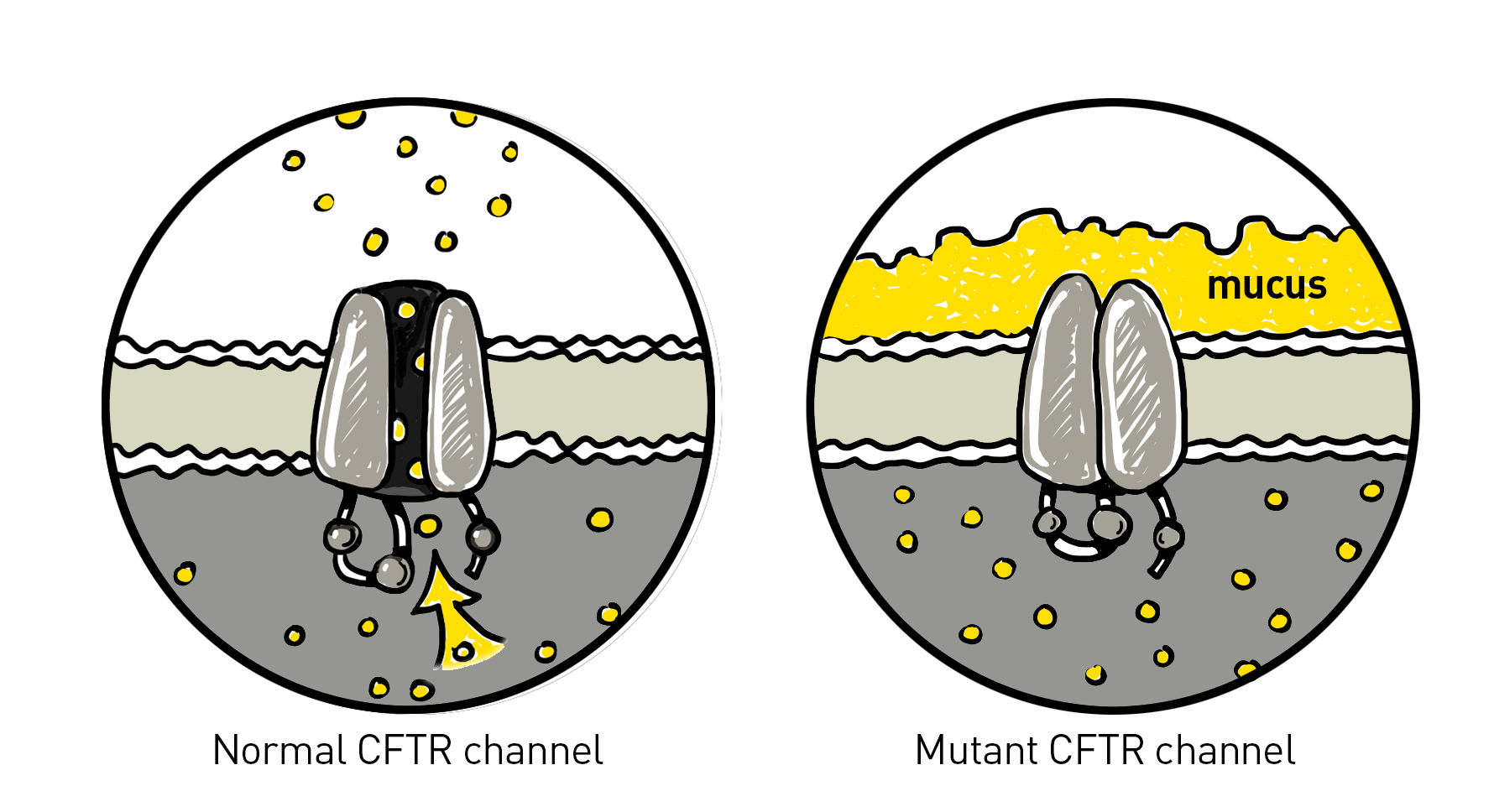

Today, we know the normal CFTR protein acts as a channel that allows chloride to move across cell membranes, which helps regulate the balance of salt and water in the body’s cells and tissues. Faulty or absent CFTR proteins cannot move chloride to the cell surface, leading to the production and buildup of thick and sticky mucus in the respiratory and digestive tracts. More than 1,700 known mutations in the CFTR gene contribute to various severities and manifestations of CF.

James grew up during significant progress in the CF field, which ultimately led to a better understanding of the disease and the development of many treatments that greatly improved the quality of life for him and other patients living with CF. However, the CFTR discovery was not the only time the field of genetics would touch James’s life; in fact, science and genetics would become a major part of his identity.

“I grew up being generally interested in science, which I think comes from growing up with cystic fibrosis and having to interact a lot with medical care and medications,” said James. “As I progressed throughout high school and college, I became interested in learning what these medications do and how the disease works. In many ways, I think my desire to learn about it was like a coping mechanism.”

His love of science led James to major in chemistry and math in college. After a brief foray into defense cost estimation, he learned about computational biology and bioinformatics. This led him to a master’s degree and his current role at HudsonAlpha Institute for Biotechnology.

At HudsonAlpha, James works in the lab of Faculty Investigator Greg Cooper, PhD lab. The Cooper lab uses genome sequencing to diagnose and better understand rare genetic neurodevelopmental diseases and disorders. Over the past decade, they’ve sequenced nearly 2,000 individuals, returning potentially informative genetic variants to about 47 percent of patients, including diagnoses to about 29 percent of patients. Staying at the forefront of genomic sequencing and analysis technology is critical for what they do, and James plays a vital role in that.

“My role in Greg’s lab is to ensure the lab’s needs are met computationally so we can take all of the data from the sequencers and use it to help make a diagnosis. I am constantly looking for new and different tools and algorithms to process that data and look for different genetic signatures of diseases to help make those diagnoses.”

Many of the individuals the lab works with are babies and young children with physical and intellectual disabilities. Although James and his colleagues at HudsonAlpha don’t work directly with CF patients, he does believe his personal experiences with CF give him a unique perspective when providing diagnoses to families.

“I know how important a conclusive diagnosis is to the individual and their family,” James expressed. “But I also know how fundamental the underlying biological knowledge is to push discoveries and new treatments for the entire disease community. Change didn’t happen overnight after the CFTR discovery, but now we have new therapies that have been transformative for many people. None of that would have been possible without that underlying knowledge.”

Before the first CFTR mutation was discovered, the life expectancy for people with CF was bleak. Early treatments aimed to keep the airways clear of mucus and aid digestion with digestive enzymes. The universal adoption of CF screening into newborn screens in the US led to earlier diagnosis and intervention, significantly increasing the overall survival rate.

Before the first CFTR mutation was discovered, the life expectancy for people with CF was bleak. Early treatments aimed to keep the airways clear of mucus and aid digestion with digestive enzymes. The universal adoption of CF screening into newborn screens in the US led to earlier diagnosis and intervention, significantly increasing the overall survival rate.

Today, therapies called CFTR modulators interact directly with the faulty CFTR protein to improve its function. They’re a game changer for a large percentage of patients living with CF, but not all. The most widely prescribed CFTR modulator, called Trikafta®, targets the most common mutation found in CF patients in the US, “deltaF508”. However, deltaF508 is not equally prevalent in all populations. Since the therapeutic does not work for some people with CF, continued research is needed to create treatments that help all CF patients.

The impact of the CFTR gene discovery and the development of new treatments for CF patients is a big driver for James in his current job. In addition to helping diagnose patients with diseases with a known genetic cause, the Cooper lab also discovers new gene-disease associations by collaborating with other researchers worldwide. The team has been a part of more than 25 collaborative publications linking dozens of genes to developmental conditions, which is critical for finding new disease treatments.

James’s experience living with CF helps him be a more empathetic scientist. His in-depth understanding of research also allows James to advocate for others in the CF community. Over the past decade, James has worked on several advocacy committees for the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation. He began his advocacy work as a member of the Adult Advisory Committee, providing feedback and leadership on different initiatives led by the CF Foundation.

More recently, James served on the Clinical Review Committee for the CF Foundation. This committee reviews grant applications for clinical research. The team of patients and family members give community feedback on the research grants submitted to the foundations. They help determine if proposed clinical trials would interest CF patients and whether studies help meet the unmet needs of the CF community.

James credits his science background with helping him better understand and appreciate the studies proposed for grant funding. “To be able to read the grant, understand what they’re trying to do, and then give very specific feedback on whether this interests me as a person with CF is powerful,” expressed James.

Through his work in diagnostic research, James also knows how important clinical trials are for advancing CF research. He has participated in several clinical trials himself.

“I think that being a scientist and having that background draws me to participate in some of the more curiosity-driven studies that don’t get quite as much recruitment because there’s not an obvious benefit to the patient,” said James.

James has also worked directly with the UAB Adult CF care team on patient care quality improvement (QI). Over the next two years, he will co-lead a working group of CF patient and family QI partners across the country.

Final thoughts

Throughout our conversation, James made it clear that both the CF and genetics fields need to continue working to make research and treatments more inclusive of all people.

“What I would love to see in the near future is an intentional drive to make the technologies we know about here at HudsonAlpha, like genome sequencing and long-read genome sequencing, accessible to more people with rare diseases,” expressed James. “Many people with rare diseases don’t live near a major research hospital with these programs, and oftentimes insurance doesn’t cover them. It is such powerful information for so many families, but it should be available for everyone struggling to find a diagnosis.”

James sees a mirror to similar challenges faced in the CF community, such as a better understanding of social determinants of health in CF care, enabling global access to transformative therapies such as CFTR modulators, and increasing recognition of CF in people of color.

“Everyone deserves life-changing CF therapies,” James says, “but to get there, we need more treatments and equitable access to them. We need to remember that there are tens of thousands of people who have mutations that cannot be treated with CFTR modulators, who couldn’t tolerate the existing medications, or who live in countries without access to these therapies.”

“In both cases,” James reflects, “it’s an exciting and hopeful era, but one that still has a lot of work to be done.”