Throughout this season of Tiny Expeditions, we learned about many groundbreaking research studies trying to ensure our future health and well-being. This included everything from forensic investigations and pandemic preparedness to climate change and personalized healthcare. All of this research requires dedicated scientists with a passion for investigating the intricacies of life.

In this episode, we shift our focus to a unique educational program preparing the next generation of scientists to tackle some of these critical challenges. Peanuts, a tasty and nutritious commodity crop, play a crucial role in global food security. However, climate change, emerging diseases, and evolving pests pose significant threats to peanut crops. To address these challenges, a forward-thinking breeding program engages students in a hands-on project to create improved peanut varieties.

The program not only imparts valuable technical knowledge but also instills a sense of responsibility and ownership in students to address real-world challenges. As they witness the impact of their work on improving peanut varieties, they become motivated to apply their skills and knowledge to other pressing issues facing society.

Join us for Tiny Expeditions Season 4, Episode 6, “Peanuts for the future: how students are collaborating to improve the legume we love,” as we explore how this educational program is nurturing future scientists who will play a crucial role in safeguarding our health, well-being, and food security while creating economically important peanut varieties for their region.

Behind the Scenes

We really enjoyed our (virtual) time with Keely Brewer, a Dothan High School biology teacher. It was instantly apparent that she was passionate about her job and her students. A self-proclaimed life-long learner, Keely told us that she loved school so much that she didn’t want to leave, so she stayed and taught.

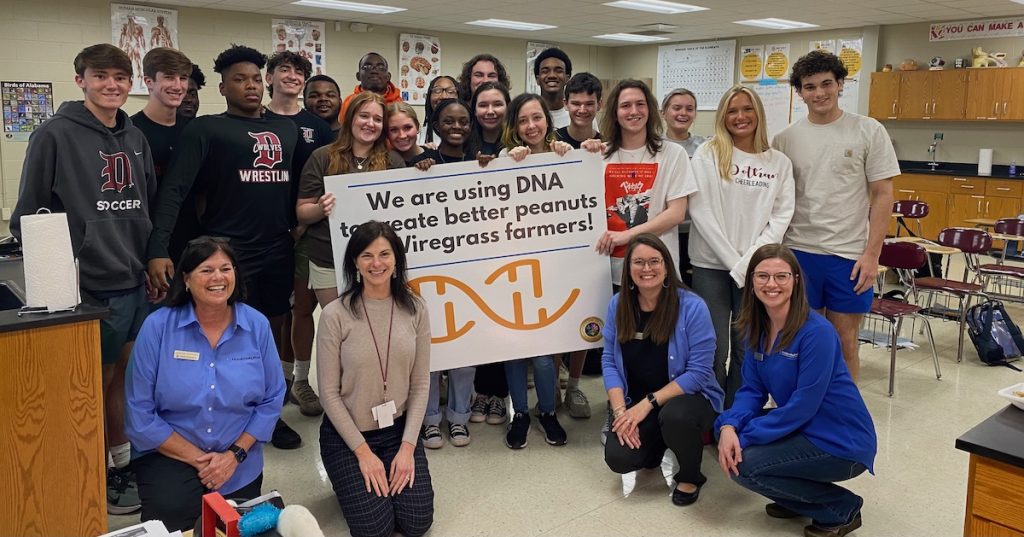

Keely’s class was part of the pilot program for the HudsonAlpha WIREGRASS Peanut Project. The acronym stands for With Innovative Regional Experience Growing Real Advancements through Student Scientists. As Keely described in the episode, the program allows students to gain real-life research experience working on a crop they all know and recognize–peanuts.

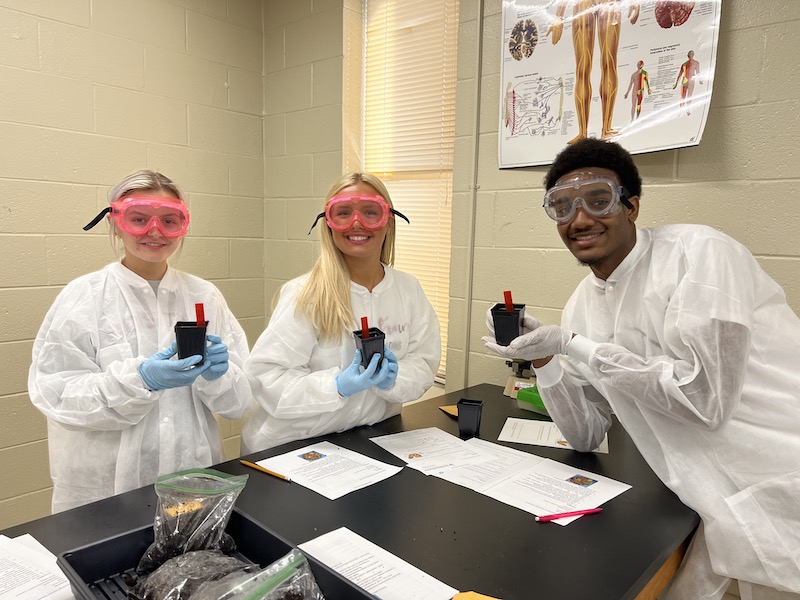

The WIREGRASS Peanut Project was developed by the HudsonAlpha Educational Outreach team and HudsonAlpha Faculty Investigator Josh Clevenger, PhD. With help from the HudsonAlpha team, students participating in the program grew peanuts from a seed. They were tasked with keeping the plant alive and ensuring it was thriving. Once the peanut plant was a certain size, they clipped leaf tissue off of the plant and extracted DNA from it.

Dothan High School students showing off the peanut seeds they planted during class.

A Dothan High School student checking in on the peanut plants growing in her biology classroom.

The DNA was sent to HudsonAlpha’s campus in Huntsville for whole-genome sequencing. This means that all of the DNA in the peanut leaf is sequenced. The DNA sequence data is analyzed using Khufu, a computation pipeline created by Dr. Clevenger and his colleague Walid Korani, PhD. Khufu helps identify small DNA sections that correlate with beneficial traits like pest resistance, drought tolerance, and elite line background. The students are the sequencing data and asked to choose the peanut plant that will be crossed to create the next generation of peanuts.

We had the opportunity to see the peanut plant the students chose this semester. Drs. Clevenger and Korani showed us around the Kathy L. Chan Greenhouse on HudsonAlpha’s campus, where the peanut plants are growing.

The peanut plant that the students chose has such good genetics that the team went ahead and made dozens of clones of the plant. Those plants will be used for the first field trial, where the peanut plants are grown outside in a field to see how they perform beyond a controlled greenhouse setting.

Chris and Dr. Clevenger in the greenhouse peanut room looking at the WIREGRASS project peanut plant.

This is a photo of the peanut plant the WIREGRASS Peanut Project students chose to move forward in the breeding program. It is growing well and was set to be harvested the week after this photo was taken.

Dr. Clevenger told us that the peanut plant had such good genetics that they made many clones of the plant. The clones are under the plastic tub. They will be grown to a certain size then planted outside in a field as part of the first field trial.

Here is a close-up of the peanut flowers Dr. Clevenger described during the episode.

Chris Powell 00:05

Welcome to Tiny Expeditions Season Four, Episode Six. Hey, Sarah. It’s the final episode of this season. So, what are we doing? What are we talking about today?

Sarah Sharman 00:15

Today we’re talking all about the tasty and nutritious commodity crop peanuts and how one educational program is teaching students all about genetics by including them in a breeding program to create improved peanut varieties. But first, let’s introduce ourselves. I’m Dr. Sarah Sharman, here to help you understand the science.

Chris Powell 00:33

My name is Chris Powell. I’ll be your narrative guide for today. And joining us one more time is…

Jordan Phillips 00:38

Hey, my name is Jordan Phillips, and I’m an intern with the HudsonAlpha Biotrain program this summer.

Chris Powell 00:43

Excellent, Jordan. So, we’re going to have a great time today. Sit back. It’s all about peanuts. All throughout the United States and across the world, really, peanuts are pretty popular. I know for me, they’re pretty popular. Sarah, I love peanuts. How about you? Jordan? Are y’all fans of the peanut?

Sarah Sharman 01:03

Yeah, I’m a fan of the peanut. It really packs a nutritional punch, so I eat a lot for breakfast.

Chris Powell 01:09

That’s a lot of Ps all together for you. How about you Jordan? Are you a fan of the peanut?

Jordan Phillips 01:16

Yeah, I like peanuts pretty good.

Chris Powell 01:17

Okay, so if you’re gonna eat a peanut, what’s your best, most favorite way to consume them?

Jordan Phillips 01:22

The main way that I eat peanuts is probably a Reese’s Peanut Butter Cup. Those are the best.

Chris Powell 01:28

Hey, no judgment here. That’s a great way to consume peanuts. How about you, Sarah?

Sarah Sharman 01:33

Yeah, for me, I really like a peanut butter and banana sandwich like that’s probably my favorite.

Chris Powell 01:38

That’s the Elvis sandwich, right?

Sarah Sharman 01:40

It’s really good. Elvis, yes.

Chris Powell 01:43

I think for me, growing up in South Alabama, they have the roadside boiled peanuts. I think that’s the superior way for me to consume peanuts.

Chris Powell 01:55

So, whether you enjoy Reese’s Peanut Butter Cups, boiled peanuts, or peanut butter and banana sandwiches, it’s easy as we’re consuming the product to forget that the product comes from somewhere. There are farmers, there are communities that are all dependent on successful harvest of the peanut.

Sarah Sharman 02:12

And peanuts sure are big business in the southeastern United States. Approximately half of peanuts grown in the US are grown, harvested, and processed within 100 miles of Dothan, Alabama. Alabama itself is home to about 900 peanut farmers who plant and harvest about 160,000 acres which yield about 400 million pounds of peanuts, and more than $200 million in revenue annually.

Chris Powell 02:37

Those production numbers are striking. That’s a whole lot of peanuts produced for us to enjoy. But it comes to us because of the diligent work of farmers and researchers who are combating the global spread of plant diseases and pests. And they have to deal with dwindling natural resources, climate change that threatens crop production, and also the increased price of inputs like fertilizers and pesticides.

Sarah Sharman 03:01

A new program in the Wiregrass region of south Alabama is using the power of genomics to develop more of these drought and disease-resistant varieties of peanuts to thrive in the Wiregrass region and beyond. One unique feature of this breeding program is that it is partially driven by high school students. To help us understand this program a little better, we talked to Dothan High School teacher, Keely Brewer.

Keely Brewer 03:24

I’m Keeley Brewer, and I’m an educator at Dothan High School in Dothan, Alabama. This is my 15th year altogether, and this will be my 8th year at Dothan. The overview of this peanut project was that the students will be able to plant the peanuts, watch the seedlings grow, and then participate in a DNA extraction from the leaves of the young seedlings. Once the DNA is extracted, it is sent back to HudsonAlpha in Huntsville for DNA sequencing. And then, once it’s been sequenced, the data is sorted so that way they can understand what particular five or six traits are present or absent in their own seedling. Then, as a class, they have to decide what traits are valuable and should be selected for in the next generation of peanuts and crossed back to the original plant. And then maybe what are some traits that are not as valuable to our area.

Keely Brewer 04:20

For Dothan, specifically, the peanut plays an important role in our economy. A lot of the kids have links to farms. Or even if they don’t have any sense of farming, because I do teach in a city or suburban area, they can still know that it’s a big part of our economy. We have everything from the peanut festival from the time they’re little kids, they see the peanut statute statues around town. You know, we always go on field trips in and around the area we’d look at farming. So, they’ve certainly heard about the importance of peanuts to the economy. This gave them a chance to actually grow peanuts, and a lot of my kids had never seen one outside of the field so to actually have one in their hand and begin to grow, that was a neat idea for them. And then to understand that the seeds change, that it’s not just the same peanut that’s grown, that if they could use genetics and produce a better product, then the farmers could earn more money, hopefully, get a better yield, it might make an impact beyond our community.

Chris Powell 05:24

Keely is a teacher at Dothan High School. But Dothan is only one of the schools involved in this project. Currently, there are four schools taking part with three more to be added in the coming year. All of these schools are in the Dothan or larger Wiregrass area.

Sarah Sharman 05:37

The schools that take part in the program sign up for a continuing relationship with the HudsonAlpha educational outreach team, led by Kelly East. The educational outreach team travels to each school to help with collection. And then, they bring the teachers to the Huntsville campus for further lab training.

Chris Powell 05:52

While the students participating in this project are doing this as part of their biology class, this is real-world experience that they’re getting inside of the classroom.

Keely Brewer 06:01

They really enjoyed it. It was a fun experience. Again, they didn’t know exactly what they were getting into because I couldn’t really prep them for what was happening that day. They loved getting to hear about the actual science that was going on. Because especially in an AP Biology class, it’s a really molecular-based class. And we are always just on the inside of the cell. They don’t necessarily see what that’s going to do in the real world to have a scientist walk in the door and say, ‘Okay, well, you know, I used to work for Mars. And this is how we worked with the peanuts.’ And this it kind of gave them a different perspective of what a scientist does. Kids really just think in terms of science, ‘oh, I can be a doctor or a pharmacist or a dentist, or I can be a science teacher,’ and then past that they don’t really know what an interest in science is going to get them as a career. So, it was a lot of fun to get to have people come in and raise students’ interest. It gave them a very real sense of what the geneticists are actually doing.

Keely Brewer 07:10

Because once the DNA was actually sequenced and it was sent off, they came back and for the third lesson, they got to look at different traits that would actually grow out in the peanuts, and they got to evaluate what would be better seed. And so it kind of gave them that sense of oh, here are some local jobs here, or some ties to our community, and some real-life examples of how genetics are used. So, I was pleased with that, I really want to always offer our kids new ideas, and then link it back to a future for them. You know, if you go off, and you decide this is interesting, and you go to college, well, hopefully one day, you can come back to this community, and there will be a job here for you. So that’s the exciting part of being involved with HudsonAlpha Wiregrass is that, hopefully, those jobs will be in the community. And so if we can get them interested and understand a way that they can relate genetics to real life, then hopefully they’ll seek that out in college.

Sarah Sharman 08:10

It turns out this program is not just benefiting the students, teachers who are often pushed beyond their limits in terms of time and effort, work hard to develop lesson plans, but sometimes they fall back on the same ideas year after year. This program is empowering them with continued education, some of it on campus in Huntsville, to incorporate new methods into their teaching.

Keely Brewer 08:32

You do kind of tend to do the same ideas every year in your classroom. And so, it’s really fun to have a fresh project and a fresh perspective, to have people come in with great ideas and great products. So that way, you can get the kids inside it, but it can also teach and train the teachers. And that’s one of the nice things is that, you know, the people at HudsonAlpha really, they contacted us and they stuck it out, and they trained us this summer, and it was really nice to have that follow-up. It wasn’t just, oh, here’s something that we can do once, and you’ll have fun with it. It’s nice to see that there’s a continuing project and that, hopefully, it can exist in different iterations for years and impact a lot of people in our community.

Chris Powell 09:17

The HudsonAlpha Wiregrass project is a great project for teaching students in the classroom about the application of genetics to agriculture.

Sarah Sharman 09:24

The educational benefits of this project are already evident. Students get to grow peanuts from a seed, take care of them, extract their DNA, and analyze actual sequence data. But the peanuts don’t get thrown away when the semester is over. The top peanut plants from each class could actually make it to a farmer’s field one day.

Chris Powell 09:44

But before we can get the peanut from the classroom to the field, we need to walk you through the process, and that begins in the lab of Abby Burch in Dothan.

Abby Burch 09:54

I’m Abby Burch, and I’m the lab manager down here at HudsonAlpha Wiregrass. I worked closely with Josh Clevenger and his theme in peanut research. Some days I am doing computer work, trying to get stuff ordered. Right now we’re trying to get our pedigree for the next season set up. I also share a lab with a class during the school year, so I have to kind of schedule my days out to where my lab work doesn’t interfere with their classwork. Even though the teacher was like, ‘No, you can come in,’ I was like, ‘No, that is not a cohesive, like, that’s not going to work for me, it’s not going to work for your students, they’re not going to learn anything if I’m in there, and I’m not gonna be able to focus that they’re in there.’ So that really took a toll on just trying to figure out how my days are going to look. But other than that, during the summer, I’ve been learning some coding with Zach Myers. And I’ve also been doing a lot of extractions, it may be libraries that we’re prepping, or you know, getting stuff ready for sequencing. That’s essentially what I’m doing is just making sure that everything is getting done running smoothly. It just really depends on the day.

Chris Powell 11:15

Abby is the perfect person to run this lab in Dothan because she was born and raised in the area in the Dothan Wiregrass area. So, she is well aware of the issues that farmers face locally.

Abby Burch 11:27

Pretty much everybody knows a farmer down here, knows somebody who does farm. You know, the growing seasons are different down here. It’s hotter for longer periods of time. But I think sometimes I wear shorts at Christmas, sometimes I don’t, just depends on the year. We only get probably about three or four months a year that are cold. So always really have to think about that. And then they have to also think about the weather patterns. Because sometimes we get a lot of rain, sometimes we don’t get a lot of rain, it’s just really dependent. But growing up down here everybody knew a farmer knew some knew of someone who farmed. When it comes to peanuts and the area that they are grown in, it really depends on the field. Certain fields have certain diseases and certain funguses that we have to kind of deal with. And unlike Georgia, Alabama does not have a whole lot of irrigated fields. They’re smaller, less irrigated. So, drought is a really big thing that we have to look at as well. But we really are just looking at peanuts and seeing what disease packages do they have? Or, what are they resistant to? And then, how do they do under drought stress? And also, what we’re wanting to do is we’re wanting to help alleviate some of these costs for farmers. So, in order to do that, we’re looking at things so they don’t have to spray as much, they won’t use as much fungicide. Then at the end, we want them to have a lot of peanuts, we also look at things like yield, we want them to make sure that they’re making money off of their product. That is what we’re doing.

Sarah Sharman 13:09

As with any new project or technology, you have to ask the question, is this going to be received well? Because as we’ve already stated, there’s a lot on the line for everyone involved.

Abby Burch 13:19

You know, the farmers are actually very receptive. They are all for it. You may have to explain a little bit. Explain it genetically modified organisms and stuff like that. You may have to just kind of go through it. But most of them know the process really well. They know their plants, you know what I mean? They know what they’re growing. They know how it works, and they’re very receptive. And the people in the community who are really wanting to see our community flourish are ecstatic. They are so happy that you know Dothan’s getting R&D because we don’t have anything like this down here. And it’s really, I think it’s really a good thing for our economies. Our city is really trying to just expand and do better, and I think HudsonAlpha Wiregrass is just a part of that.

Chris Powell 14:05

In the future, all of the Peanut Project work will be done in the new lab at the Wiregrass Innovation Center. Until then, much of the work is done at HudsonAlpha’s Huntsville campus. So, we caught up with Dr. Josh Clevenger and Walid Korani at the HudsonAlpha greenhouse to learn more about the research side of the project and to see some of the students’ peanut plants.

Josh Clevenger 14:24

Yeah, so we’re entering the the mid hallway of the greenhouse now and it has double doors on each side and that helps us keep pests out. And so right now we’re going to be opening the door into the room where we have some of the Wiregrass peanuts that are maturing now. So, you guys have to put this stuff on your shoes. This is bleach and I won’t make you do that but we got to do alcohol on your hands. So these massive giants in these pots are actually the plants that were selected by the students in the classroom. And so, what we did is after they were selected, we brought them into this greenhouse room. And we made a cross with a really awesome elite variety that was just released this past year that has really strong fungal resistance. And so, all those plants have been crossed. And those peanuts are just now developing, and those peanuts will be harvested. And then the students in the fall and the spring will be actually working with those to decide to do the next cross.

Chris Powell 15:36

How close to harvest are we now?

Josh Clevenger 15:38

Actually, we can probably harvest these next week. So, we’re about ready to harvest them. Once you made the cross, it’s about 45 days until they’ll mature, and you’ll harvest them. So, what’s really interesting before we go is if you look at this peanut flower, each one of these flowers, you have to take the male parts off because in the morning, basically as soon as it opens if the pollen is viable, it’s going to pollinate that stigma. And so, at night, we have to come in very carefully and like pull back this flag and these sepals, and then take the male parts out. So, in the morning, when it opens, we can take pollen from the plant that we want, and then just gently put it on there. But it really likes the humid environment. So you have to keep all of this in good shape, so that you can put it back together and it can have that nice snug environment. And just one of these flowers makes one seed. So unlike grasses or corn, where you just dump pollen on top, and you get a whole thing of seed, or tomatoes, which I used to work on, if you want one seed, you have one flower. So, it’s hard work. But it’s pretty hot here. Let’s go talk out in the air conditioning.

Sarah Sharman 16:55

For as long as humans have been domesticating crops, they have been breeding the best, strongest tastiest plants together to make elite varieties. The only difference now is that we can look at the plants’ genomes to know what traits they’ll exhibit before they’ve even matured, speeding up the process and making it more efficient.

Josh Clevenger 17:14

All right, so what we actually did so we looked at those plants we saw the we cross them, how did we select them? How did the students select them? And what did they select for? So, this entire improvement program is based on backcross breeding, which means that you’re trying to take a plant that has a very valuable trait that you can select for with a marker in the genome. So, it’s like a piece of DNA that has a variant in its gene and selects for that and then backcross it to a line that you know the farmers will grow and is what we call elite genetics. And then, just select for the background of the elite line and then those specific traits that you have markers for. We actually are able to do this using whole genome sequencing because in our lab, we developed with my partner, Walid Korani, something called, and you need to say it correctly.

Walid Korani 18:06

Yeah, Khufu.

Josh Clevenger 18:08

And do you want to explain exactly what that actually entails?

Walid Korani 18:13

Khufu is a big platform for genetic analysis, one part of it to take the raw data and try to get information from it. For example, for that project, so we have plants and we need to know the polymorphic loci between these plants and try to connect which loci is the best choice for what we need, and use this later on for doing genetic selection. So once the data has been selected for the first round, it’s sent for sequencing and comes back as raw data. But this raw data is nothing unless it’s strong for analysis to go through Khufu and get the output and use this output again for the next season to doing quick selection without getting for phenotypic analysis.

Josh Clevenger 19:00

Walid is a very talented computational biologist, who thinks in binary, so ones and zeros all the time. So if I translate what he just said, we are actually able to use the informatics platform to look at very low coverage sequencing of every line and actually look at the genotypic variation across their entire genomes. So in sort of an interesting way to think about it, this breeding program that the students are participating in is the only breeding program in the world where the selections are only based on sequencing because of our ability to do that. So that’s what really makes us unique. We’re not just teaching them about breeding and actually breeding with them, but we’re doing it in a way that’s completely cutting-edge because of our ability here at HudsonAlpha to do that work. And so, if we translate that a little bit, we have targets in the genome that we know are going to tag very strong traits resistance to fungal diseases, resistance to viruses. is tolerance to drought, things like that. And so we can look at every plant and know exactly what their phenotype might be for those specific ones. And then look for millions of markers across the genome to say how much of this plant is also that elite line that we really like. And so, we can pick ones that say stack, what we call stack, which includes many high-value traits, four or five different high-value traits, and then 90% of the elite background. And that is that is really the power and gives us the speed to develop these very specific tailor-made plants very quickly.

Chris Powell 20:33

Let me ask a question about the students in Dothan. They have access to some information to be able to vote on what plants you’d like to see cross. How much of that information because obviously, what you’re telling us about is going to be well beyond what they’re going to be able to have. So how much information do they actually have in order to have input on this?

Josh Clevenger 20:54

So our goal as we get sort of mature in the program is to actually have computational modules where the students are actually analyzing all of the data from start to finish. Right now, what we give them is we tell them, if those plants have those specific beneficial alleles. So, the alleles we know will confer some sort of resistance or trait that we’re interested in, and also how much of their background matches in an elite variety. So, they say this line is hi-oleic and has resistance to a virus and resistance and nematodes. And it’s 95% of this really high-level agronomic variety and so that they can look at that and say, that is aligned that I want to move to the next generation. What we’re doing here, this breeding program, using sequencing to select for high value traits within peanut to accelerate that improvement, really, that is the outcome of a dream of coupling individuals that were leaders in the peanut community that came together and said, okay, the human genome has been sequenced. The arabidopsis genome, the rice genome, we should do peanut, which actually is a ridiculous thing to think, because peanut exponentially is more complex than those other genomes.

Josh Clevenger 22:06

And so at that time, in 2008, it was kind of absurd to like go for that, you know, that’s like really next level stuff. But they got the industry involved with the promise of we can accelerate improvement for our growers and for our next generations. And so, they actually set out over the course of three to four years to get buy-in from every segment of the peanut industry is completely private funded. So the grower checkoff and the National Peanut Board put in a third of the money, the American Shellers Association, who are the ones that shell the peanuts, and some manufacturers put in a third. And then the manufacturer is mostly covered by the big players, Mars Wrigley is the biggest one in that. And they also put a third, and all that money came together and formed the International Peanut Genome Initiative, which from 2010, until actually just this year, was active and met every year at large international meetings with all the players around the world to collaborate and share with that ultimate goal of sequencing the peanut genome. Now from 2010, when they got the money, until 2019, that wasn’t possible because it was too complex to assemble. HudsonAlpha got early access to Pacific Biosciences long-read sequencing. And so, in 2017, HudsonAlpha was brought in, and that actually gave us the ability to sequence the peanut genome. So, I was one of the lead authors on that paper. That’s when I first met Jeremy Schmutz and the GSC and those folks at HudsonAlpha. And so, really, it’s apropos that this entire large initiative with the dream of accelerating peanut improvement using genomics and the genome comes back here to HudsonAlpha. And so those students, what I tell them is I say, look, there’s maybe 100 to 200 high-level scientists across the world that worked for almost 15 years on the dream that you could do this here today. And this is the outcome of that having markers and having the ability to use genomics to make selections to do that faster. That’s why we have that ability. And so it’s really just an amazing story of folks that said, we think we should do this. We don’t know that we can and then continuing to push science and collaboration across the world to really get this done. Because without all of that, we wouldn’t be able to do this here.

Josh Clevenger 24:31

So, and then piggybacking off of that, here at HudsonAlpha, we have partnerships with a lot of folks in the USDA, and in Mars and other global organizations. And so we’re actually using our genomic ability to help those folks breed. But also, companies like Mars that are trying to produce drought tolerant, low aflatoxin, disease resistant varieties all over the world because they’re global and they buy peanuts everywhere. Peanuts are grown because the United States is the only country at the moment that freely shared germplasm. In the Wiregrass, what we have the ability to do is develop varieties that can be then shared globally. And a lot of the projects that we work on, and we’re talking South America, Africa, Australia, Asia, all of those places, we can develop peanuts here that then can go there and help in those breeding programs either as germplasm that they use or as actual varieties. So peanut is really interesting. It’s a day neutral plant, meaning it will flower with any daylight. And so, it does really well in different environments. It’s really strange, the whole country of Australia, okay, they have peanut company, and make some of the best roasted peanuts I have ever had in my life called Picky Picky Peanuts. Nobody bought them, so they don’t make them anymore. And I’m very frustrated by that. But they grow varieties that were released in Florida. They don’t do anything to them. They were bred and released in Florida, and they just licensed them, and they grow them in Australia. So we really have a big opportunity here. It’s not like soybean, corn, and things, where we have to do a lot of local breeding. We have a big opportunity for these students in this program and for us to develop enough varieties that can directly be grown in other countries.

Sarah Sharman 26:18

The Wiregrass Peanut Project is just getting started. We’re excited about the possibilities for the farmers in the Wiregrass and beyond, as well as the impact on the region and the students who are experiencing the wonders of genetics.

Chris Powell 26:31

Before we let you go on this episode, though, we need to get back to the beginning. There was a little bit of a controversy and we wanted to address with one of our panelists, what’s the best way to enjoy a peanut?

Abby Burch 26:44

It is a very important question and boiled every day all day long. That is my favorite way to eat a peanut.

Chris Powell 26:51

So, there you have it. It’s science. Boiled peanuts– the best way to enjoy a peanut. But that’s okay. If you like Reese’s peanut butter cups or sandwiches, that’s fine. Just know that researchers are making sure that you’re going to have access to those treats going forward.

Sarah Sharman 27:06

And that’s a wrap on season four. But don’t worry, we’re already working on season five. So, stay tuned. It’s gonna be a lot of fun! In season five, we’re getting pop cultured. We’ll look at how genetics is represented in iconic films, TV, and music to see what they got wrong and, maybe, what they got right. We hope you’ll join us.

Chris Powell 27:25

Thank you for joining us on this tiny expedition into the peanut project that is impacting the Wiregrass region and beyond.

Sarah Sharman 27:32

And thanks for joining us this season and exploring the ways in which genetics and biotechnology are helping combat global challenges and create a healthy world for tomorrow.

Chris Powell 27:41

Tiny Expeditions is a podcast about genetics, DNA and inheritance from the HudsonAlpha Institute for Biotechnology. We’re a nonprofit research institution in Huntsville, Alabama.

Sarah Sharman 27:51

We’ve got a campus full of scientists doing public research alongside companies developing products and services, all with one aim: to translate genomic discoveries into real world applications that make for a healthier, more sustainable world. That’s everything from cancer research to agriculture for a changing climate.

Chris Powell 28:08

If you find this podcast interesting, please rate review, like and subscribe on the podcast app of your choice then tell somebody that you listened to this interesting little story about genetics. Knowledge is better when you share.

Jordan Phillips 28:19

Thanks for joining us