by: Sarah Sharman, PhD, Science writer

In the late 1960’s, peanut breeders at North Carolina State University bred several peanut lines with remarkable pest and disease resistance. Unbeknownst to anyone at the time, these peanuts would go on to contribute beneficial traits to cultivated peanuts throughout the world. Thanks to some modern-day detective work and genetic sleuthing, a team of scientists, including HudsonAlpha Institute for Biotechnology Faculty Investigator Josh Clevenger, PhD, have mapped out these peanuts’ international trek around the world. The study was recently published in PNAS.

Tracing the genetic legacy of a North Carolina peanut

This story begins with a peanut mystery — several years ago, breeders began to suspect that a peanut line in Brazil, long believed to be of pure cultivated peanut pedigree, may actually owe its exceptional pest resistance to a wild species of peanut. Pest resistance, as well as resistance to fungi, toxins, and weather events such as drought, are highly valuable traits in cultivated peanuts. Breeding and growing plants having these beneficial traits could mean the difference between a successful harvest and a loss of livelihood for peanut growers.

Peanut has narrow genetic diversity, meaning there are not a lot of different genes to target for breeding beneficial traits. In order to overcome the genetic limitations, breeding programs try to strategically breed peanuts with their wild, uncultivated relatives to increase genetic diversity and expand the range of favorable adaptations obtained.

However, breeding wild peanuts with cultivated peanuts is difficult because wild peanuts are diploid (two sets of each chromosome) while cultivated peanuts are tetraploids (four sets of each chromosome). Many peanut breeding programs have developed methods to cross wild and cultivated peanuts. A team of scientists and breeders, led by the University of Georgia’s David Bertioli, PhD, and Soraya Leal-Bertioli, PhD, suspected that one such cross of wild and cultivated peanuts may have given the Brazilian peanut line its pest resistance.

However, breeding wild peanuts with cultivated peanuts is difficult because wild peanuts are diploid (two sets of each chromosome) while cultivated peanuts are tetraploids (four sets of each chromosome). Many peanut breeding programs have developed methods to cross wild and cultivated peanuts. A team of scientists and breeders, led by the University of Georgia’s David Bertioli, PhD, and Soraya Leal-Bertioli, PhD, suspected that one such cross of wild and cultivated peanuts may have given the Brazilian peanut line its pest resistance.

The team set out to determine if the Brazilian line, along with other high-quality peanut lines around the world, indeed received genetic contributions from wild peanuts. To begin, the scientists identified hundreds of small genetic variants, called single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), unique to the wild peanut genome. By searching the genomes of cultivated peanut lines for these SNPs, the scientists were able to determine which portion of the genome, if any, came from wild peanuts.

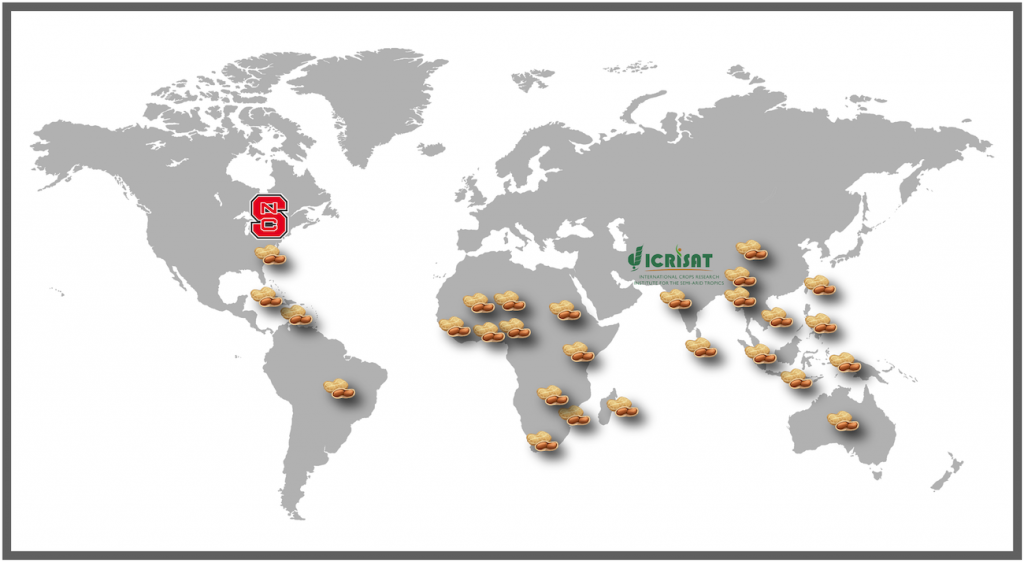

“Through our analysis we found 251 peanut lines and cultivars distributed throughout 30 countries that carried wild peanut genetic material,” says Bertioli. “Surprisingly, despite the widespread nature of the peanut lines, an overwhelming majority of the genetic influence from wild peanuts was actually traced back to peanuts created here in the United States at North Carolina State University.”

So how did the NC State peanut gain its international reach?

Turning from their genetic sleuthing to some good old-fashioned Sherlock Holmes-esque detective work, the team set out to try to track the movement of the NC State University peanut line. The team scoured over personal communications, lab records, reports, and published papers to piece together a history of these peanuts.

In the late 1960’s, breeders at NC State University bred the wild peanut A. cardenasii GKP10017 with a purple-seeded cultivated peanut A. hypogaea. A decade later, after the offspring had been crossed for several generations, Dr. H. Tom Stalker discovered that some of them were completely compatible with cultivated peanuts.

He field tested the plants at NC State, selecting those that were resistant to early leaf spot fungus. The best early leaf spot resistant peanut lines were selected and bred with other elite peanut lines to create a series of 18 new peanut lines (referred to as CS lines) with improved resistance to common peanut pests and diseases.

During the winter of 1978/1979, scientists at NC State University sent a shipment of seeds to the International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-arid Tropics (ICRISAT) in Hyderabad, India, upon the request of visiting scientist Dr. Phil Moss, Principal Scientist at ICRISAT who ran their peanut wild species program. Among the shipment were 28 peanut lines from the breeding of A. hypogaea and A. cardenasii GKP10017. The peanuts were field tested in India and showed improved pest and disease resistance.

In 1984, Dr. Moss returned to NC State University and brought back some of the peanut lines that had been field tested and selected for late leaf spot fungus in India. At the end of his sabbatical, he requested the CS lines be sent to ICRISAT for field testing there. Upon Phil’s retirement, the remainder of the CS lines were sent to the ICRISAT germplasm bank for future use and distribution.

In 1984, Dr. Moss returned to NC State University and brought back some of the peanut lines that had been field tested and selected for late leaf spot fungus in India. At the end of his sabbatical, he requested the CS lines be sent to ICRISAT for field testing there. Upon Phil’s retirement, the remainder of the CS lines were sent to the ICRISAT germplasm bank for future use and distribution.

And so began the international journey of the CS peanuts from NC State University. Because of ICRISAT’s strong belief in the open sharing of cultivated crop plants to improve agricultural practices around the world, they helped to distribute the CS peanut lines to at least 28 other countries across the world, initially sharing it with breeding programs in Australia (1986), Niger and Mali (1989-1991), and Brazil (1992).

“It is amazing to think of a young Tom Stalker, peering into his microscope, being fascinated with understanding how chromosomes from different peanut species behave in the same cell, not fully understanding that his work would contribute to the betterment of millions,” says Clevenger.

Impact and future implications of the wild peanut genome

This study uncovered the global scale of genetic influence of the wild peanut species A. cardenasii GKP 10017 on the cultivated peanut crop A. hypogaea. Even though the wild genetics became mostly forgotten or unrecorded over time, the usefulness of the improved lineages ensured their continued use and dissemination to other breeding programs.

Cultivated peanuts with genetic contributions from the wild peanut have been providing improved food security and reduced use of fungicide sprays to peanut growers across the world for several decades now. Low-income and small-scale farmers who are less able to use fungicides to control leaf diseases are especially benefited. Many of the world’s poorest and most food insecure people who rely on peanuts as a crop in Asia and Africa rely on these peanut lines.

The use of these peanuts in larger-scale farms delivers environmental benefits from reduced applications of fungicide and the accompanying reduction in use of fuel and carbon dioxide emissions, while at the same time providing economic benefits of increased yields and decreased production costs.

“This work not only emphasizes the importance of biodiversity to crop improvement but also highlights the importance of seed exchange and international collaborations on the continued diversification of crop genetics,” says Clevenger. “The free exchange of seeds, mainly facilitated by ICRISAT in this case, allowed these valuable pest resistances to spread and be utilized worldwide.”