An Everyday DNA blog article

Written by: Sarah Sharman, PhD, Science writer

Illustrated by: Cathleen Shaw

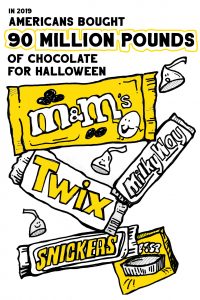

Trick or Treat! In 2019, Americans spent $2.6 billion on candy for Halloween alone. While I enjoy most types of candy, I remember as a child it was like hitting the lottery if you received a full-size candy bar in your trick-or-treat pumpkin. It turns out, I am not alone in my love of chocolate. According to a poll from the National Confectioners Association, Americans prefer chocolate over non-chocolate treats.

However, the chocolate of today is nothing like the chocolate of the past. Throughout much of its history, chocolate was a bitter beverage, not the sweet treat we know today. Let’s learn about the history of chocolate and how scientists are ensuring that our modern-day chocolate treats stay around for many years to come.

A brief history of chocolate

Chocolate is made from the fruits of the cacao tree, which are native to Central and South America. The Olmecs of southern Mexico are thought to be the first to use cacao beans for chocolate, possibly as early as 1500 B.C. Early chocolate was quite different from the bonbons and peanut butter cups we enjoy today. Mesoamericans would prepare a chocolate beverage by grinding roasted cacao beans and mixing them with corn meal and chili peppers. Now this is not a relaxing cup of hot cocoa that you might drink at the ice-skating rink, but a bitter and invigorating foamy concoction.

Mesoamericans loved their chocolate, believing that it was gifted to humans by a feathery snake-like god known as Kukulkan to the Mayans and Quetzalcoatl to the Aztecs. Ancient civilizations used cacao beans as currency, drank chocolate at fancy feasts, and even used the beans in rituals.

Mesoamericans loved their chocolate, believing that it was gifted to humans by a feathery snake-like god known as Kukulkan to the Mayans and Quetzalcoatl to the Aztecs. Ancient civilizations used cacao beans as currency, drank chocolate at fancy feasts, and even used the beans in rituals.

It is unclear when and how chocolate made it to Europe but there is consensus that it arrived in Spain first. By the late 1550’s it was a much-loved indulgence in the Spanish court. Spain began importing cacao as early as 1585, followed shortly by other European countries that had learned about cacao. Europeans did not have a taste for the traditional Aztec chocolate drink so they developed their own varieties of hot chocolate with cane sugar, cinnamon, and other flavorings.

For much of the 19th century, chocolate was enjoyed as a beverage mixed with milk or water. However, the world of chocolate was forever changed in the 1820s when Dutch chemist Coenraad Johannes van Houten discovered a way to treat ground cacao beans with alkaline salts to make a powdered chocolate that was easier to mix with water. He also invented the cocoa press which separated cocoa butter from roasted cocoa beans to inexpensively and easily make cocoa powder.

Thanks largely to the cocoa press and other technical advances in chocolate making, by the 20th century chocolate was no longer an indulgence solely for the elite classes. It was being mass produced and had become a treat for the public.

How is chocolate made?

Now that we know where chocolate comes from, let’s learn how it is made. The large, football shaped fruits of the cacao tree are called pods and each pod contains around 40 cacao beans. After harvesting the pods from the cacao trees, growers remove the beans from within the hard shell of the pod. Raw cacao beans are bitter so they are fermented to improve their flavor. Yeasts and bacteria on the beans digest the pulp in the pods which aids in converting sugars in the cacao beans into acids that decrease the overall bitterness of the beans. Molecular compounds that give the beans additional flavor are also produced during the process.

After fermentation, the beans are cleaned and roasted. Roasting drives out volatile acidic molecules that give the beans a nutty, acidic flavor. Different flavor profiles can be achieved by roasting beans at different temperatures and for different amounts of time. The roasted beans are ground to produce a paste. The paste is pressurized to produce two components known as chocolate liquor and cocoa butter.

After fermentation, the beans are cleaned and roasted. Roasting drives out volatile acidic molecules that give the beans a nutty, acidic flavor. Different flavor profiles can be achieved by roasting beans at different temperatures and for different amounts of time. The roasted beans are ground to produce a paste. The paste is pressurized to produce two components known as chocolate liquor and cocoa butter.

Different types of chocolate are produced by blending the chocolate liquor and cocoa butter in varying ratios with other ingredients like sugar, milk powder, and vanilla. Dark chocolate is made with at least 70 percent chocolate liquor and butter, while milk chocolate is made with only about 40 percent. White chocolate is made from at least 20 percent cocoa butter without adding any of the chocolate liquor.

Soil, climate, and processing all affect the flavor profile of cacao beans. For this reason, many luxury chocolatiers use beans that are sourced from a single cacao bean grower. Cacao beans can carry flavors ranging from nutty to floral to fruity. Part of chocolate’s appeal is that it can be combined with so many other flavors like caramel, fruit, and peanuts.

Will we ever see a world without chocolate? Not if science can help it.

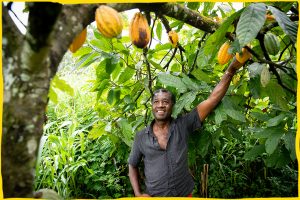

Today, most of the world’s cacao is produced in West Africa. Cacao trees grow only in a slim band of tropical rainforests 18 degrees north and south of the equator. Many of the cacao trees are grown on small, family owned farms. The livelihood of these farmers and their families is reliant on a successful cacao harvest. Unfortunately, cacao has many environmental and pest foes.

Today, most of the world’s cacao is produced in West Africa. Cacao trees grow only in a slim band of tropical rainforests 18 degrees north and south of the equator. Many of the cacao trees are grown on small, family owned farms. The livelihood of these farmers and their families is reliant on a successful cacao harvest. Unfortunately, cacao has many environmental and pest foes.

Rising temperatures from climate change threaten to destroy the only environment in which these trees thrive. Cacao trees are also vulnerable to pests and fungal infections. Witches’ broom disease and frosty pod rot disease are two serious diseases caused by aggressive fungi. Witches’ broom disease eradicated most of the cacao trees in Brazil in the 1990’s. Frosty pod rot disease is equally as devastating, destroying as much as 90 percent of the beans in a harvest year.

Because there is no cure or effective treatment for these diseases, scientists are trying to develop cacao trees that are resistant to them. However, it takes three to five years for a cacao seed to become a fruiting tree. This creates a challenge for researchers who study the genetics of cacao plants because they have to wait years to determine if a tree contains the genes for specific traits.

Researchers like HudsonAlpha Institute for Biotechnology Faculty Investigator Josh Clevenger, PhD, are trying to speed up the process of determining if a cacao tree contains genes that provide a survival advantage in the face of environmental or pest threats. While Clevenger mainly focuses his research efforts on chocolate’s best friend the peanut, he and collaborator Walid Korani, PhD, developed a high-fidelity pipeline that could help cacao research by quickly and accurately mapping beneficial traits like pest and drought resistance to genes.

To learn more about how scientists like Dr. Clevenger are trying to save our favorite candy bars, listen to Season 2, Episode 2 of HudsonAlpha’s podcast Tiny Expeditions.