by: Sarah Sharman, PhD, Science writer

Imagine sitting in the middle of an arctic tundra in Siberia seeing nothing but white all around you. It is cold and windy and you have the sense that there are snow white predators stalking you, camouflaged into the landscape around you. Suddenly, dark dogs pulling a sled streak across the horizon, in stark contrast to the white, icy world.

It turns out this scene may have been a reality to people living in Siberia 9,500 years ago. But what if I told you that genomics, not a historian or archaeologist, helped paint this picture from millenia ago? Although there are only ancient skeletal remains of the Zhokhov island dog from Siberia, whose genome was sequenced in 2020, genomic sleuthing now suggests that some of the ancient sled dogs were black in color – unlike the arctic white wolves to which they are closely related.

In a recent publication in Nature Ecology and Evolution, a group of scientists from UC Davis, University of Bern, and the HudsonAlpha Institute for Biotechnology, identified a genetic element that controls dog coat color and used it to trace domesticated dogs back to their ancient ancestors.

Genetic elements responsible for coat color

The dizzying array of different shapes, sizes, and colors in dogs is thought to have arisen by mutation and artificial selection during the process of domestication from modern wolves over the last ~20,000 years. Studying the genetic basis of dog diversity has implications for developmental and evolutionary biology, and helps us understand more about the relationship between humans and their companion animals.

In many mammals, coat color patterns arise through the regulation of a gene called Agouti (ASIP). It encodes a signaling molecule that causes hair follicle pigment cells to switch from making eumelanin (black or brown pigment) to pheomelanin (yellow to white pigment). While genetic variation in ASIP has been shown to affect color patterns in many mammals, its involvement in dog color patterns is complicated, in part because of the complexity of different dog pattern types.

Danika Bannasch, DVM, PhD, Professor of Population Health and Reproduction at University of California Davis, and Chris Kaelin, PhD, a senior scientist at HudsonAlpha in Greg Barsh’s research group, worked together to solve this dog genetic puzzle.

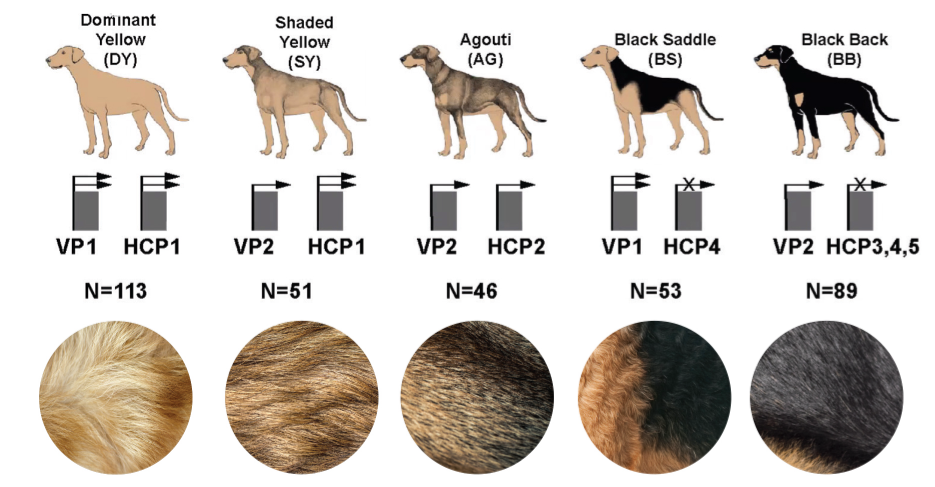

Through the analysis of dog skin samples and publicly available whole genome sequencing data, the team determined that variants in two promoters of ASIP, ventral promoter (VP) and hair cycle promoter (HCP), control coat color in different parts of a dog’s body. Genetic variation in the promoters explains five distinctive dog color patterns—dominant yellow, shaded yellow, agouti, black saddle, and black back.

Two different variants in the VP promoter (VP1 and VP2) and five different variants in the HCP promoter (HCP1-HCP5) were identified. Different combinations of the promoter variants create different fur patterns.

“Dogs with the ‘black back’ color pattern have solid black bodies but yellow paws and faces,” says Kaelin. “ The pattern is caused by mutations that turn off the hair cycle promoter, which prevents ASIP expression in the body of the dogs, coupled with a grey wolf-like configuration at the ventral promoter, which leads to ASIP expression in the paws and face.”

Evolution of coat color

Kaelin and Barsh expanded this analysis to explore genetic relationships between the ASIP variants by comparing modern dogs, wolves, and ancient wild dogs. Through their studies they uncovered a surprising connection between dogs, wolves, and an ancient wolf-like species that is now extinct.

The scientists discovered that the ASIP promoter configuration in dominant yellow dogs, common in Basenjis and Boxers, is different from the “wild-type” configuration in grey wolves, but nearly identical to arctic wolves from Ellesmere Island and Greenland where all wolves are white. This suggests a common origin of dominant yellow coats in dogs and white coats in wolves.

By creating phylogenetic trees showing evolutionary relationships between dogs, wolves, and 8 other wolf-like species, the team showed that the dominant yellow allele in dogs and wolves is much older than either species, at least 2 million years, and therefore represents “ghost DNA” from a mysterious wolf-like species.

“A small amount of Neandertal DNA is found in almost all human genomes,” says Barsh. “The dog story is similar, except the ASIP DNA in white wolves and yellow dogs is about 10 times older than Neandertal DNA, and we know what the ASIP DNA does—it causes a light coat.”

That brings us back to the Zhokhov island dog. By analyzing the dog’s genome, Barsh and his team found that the ASIP variant combination suggested this sled dog that lived 9,500 years ago exhibited a black back color pattern, allowing it to be easily distinguished from white colored wolves in an arctic environment.

The work was a large collaboration led by the research groups of Bannasch at UC Davis, Barsh and Kaelin at HudsonAlpha, and Tosso Leeb, PhD, at the University of Bern. To learn about the history of this project, please read Barsh’s “Behind the Paper” blog post here.