An Everyday DNA blog article

Written by: Sarah Sharman, PhD, Science writer

Illustrated by: Cathleen Shaw

If you’ve ever been to the doctor, you understand that the new patient process can be tedious. The last thing you want to do when you are sick is fill out pages upon pages of information about yourself, your insurance, and the reason for your visit. Perhaps the most time-consuming part of the intake process is the family health history, which you may have filled out without even knowing what it was called.

Many times, this looks like a chart containing a laundry list of common diseases and disorders with columns next to them labeled with family members like mother, father, sibling, maternal grandfather, maternal grandmother, and so on. You are instructed to check the box if you know that any of your family members were ever diagnosed with any of the listed diseases.

While it may seem tempting to skip this part of the new patient paperwork, having a complete and accurate family history is oftentimes important for the diagnosis and prevention of many diseases. Let’s discuss why your family health history is so important and the types of information that you can learn from it.

What is the importance of a family health history?

It has been long recognized that common diseases like heart disease, cancer, and diabetes, as well as rare diseases like hemophilia, cystic fibrosis, and sickle cell anemia, can run in families. If one of your parents has high blood pressure, you or your sibling could also have an increased risk to develop high blood pressure in your lifetime. For this reason, a family health history is a powerful tool in a physician’s toolbox.

The information in a family health history can help your physician gain a better picture of your past and help predict your future. Your family health history can help inform many decisions in your healthcare journey. It can be used as a tool to guide decisions about genetic testing for you and any at-risk family members. For example, if your mother’s side of the family has a high incidence of cancer, your doctor may recommend earlier or more regular screening based on your family health history.

For families affected by a disease, an accurate family health history can be used to establish the pattern of transmission and predict which family members are most likely to be affected. This allows those individuals who may be at an increased risk of developing the disease to talk with their doctors about screening options or preventative care.

Individuals in the midst of a diagnostic odyssey for an undiagnosed illness may benefit from sharing their family health history with their doctor. Even if there is no evidence of heritable disease in the family health history, the information can still help the doctor narrow down the list of possible diseases that fit the individual’s symptoms.

How do you construct a family health history?

Now that we know the importance of a family health history, let’s talk about how to pull together that information. An ideal family health history includes at least three generations of family members, though information about any of these close relatives can be useful. This means information about yourself and your siblings, your parents and their siblings, and their parents (your grandparents), although including additional relatives may improve the accuracy and utility of the history.

Doctors, genetic counselors, or other medical practitioners can help you put together a family health history. They will ask you to provide information about your family’s origin, racial and ethnic background, the health status of each family member in your history, the age and cause of death for any deceased relatives, and pregnancy outcomes for yourself and any relevant female relatives.

You may be wondering where you get all of this information to be able to help your doctor create a robust family health history. For starters, talk to your family. Some people may be hesitant to discuss their health with others, but you can explain to them that the family health history might also benefit them and their medical plan. Ask questions like, ‘Do you have any chronic diseases like heart disease or diabetes?’, ‘Do you have a health condition like high blood pressure or high cholesterol?’, ‘Have you ever had other serious diseases like cancer or a stroke?’, and “At what age did you find out you had each of these diseases?’.

Record the information so that you can update it at your next doctor’s visit. Keep track of any new health information you learn from your relatives so that you can keep an accurate, up-to-date health history.

One way that doctors and genetic counselors often record a family health history is through a chart called a pedigree. It is basically just a family tree that tracks the presence of a disease through the generations. Pedigrees also help doctors visualize patterns of inheritance to determine if a disease is inherited in a dominant manner where every generation has the disease, or in a recessive manner where every few generations have the disease.

What can you do with the information from your family health history?

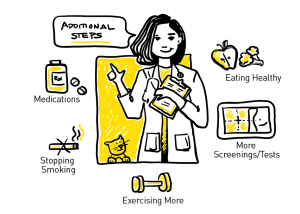

So you’ve gone through all of the steps of constructing a family health history and discussing it with your doctor, now what do you do with the information you learned? Although you can’t change your family health history, there are sometimes steps that you can take to lower your chances of getting the disease or prolong the time period before you get the disease. Let’s pretend that your family health history shows that multiple family members have heart disease. Equipped with this information, you can make lifestyle changes like smoking cessation, exercising more frequently, and eating a healthier diet, that might delay or eliminate the chance that you also get heart disease.

Your doctor may also want to discuss additional steps you can take based on your family health history. This could include early or more regular screening for the disease. For example, many organizations recommend screening for colorectal cancer and breast cancer beginning in a person’s 40s. If your family history reveals multiple close relatives with colorectal cancer or breast and/or ovarian cancer, your doctor might recommend screening at an earlier age or at a more frequent rate. Additional screening outside of the current guidelines may also be recommended. In the case of breast cancer, women with a strong family history might also receive regular MRIs in addition to mammograms.

Your doctor may also want to discuss additional steps you can take based on your family health history. This could include early or more regular screening for the disease. For example, many organizations recommend screening for colorectal cancer and breast cancer beginning in a person’s 40s. If your family history reveals multiple close relatives with colorectal cancer or breast and/or ovarian cancer, your doctor might recommend screening at an earlier age or at a more frequent rate. Additional screening outside of the current guidelines may also be recommended. In the case of breast cancer, women with a strong family history might also receive regular MRIs in addition to mammograms.

In some cases, your doctor may suggest that you or a relative undergo genetic testing to gain a more complete picture of the potential heritable condition that runs in your family. A complete family health history coupled with a genetic test can help you and your doctor put together a powerful screening and treatment plan for your future.

But what about individuals with less than complete family histories?

There is great power in having a full picture of your family’s health history. But what about individuals who do not have access to their family history? Adoptees, individuals who are estranged from their families, children of gamete donation, and children from families where the paternity is unknown are all groups of individuals who might not have the benefit of a robust family health history.

These individuals often turn to genetic testing to fill in the missing pieces of their family health history. Thomas May, PhD, is a professor of bioethics at the Elson S. Boyd College of Medicine at Washington State University and a faculty investigator at the HudsonAlpha Institute for Biotechnology. In his role as a bioethicist, Dr. May has focused a large part of his career on determining how to equitably and most efficiently use genetic testing to help adoptees gain a more complete picture of their health.

Dr. May is part of a large consortium of experts in genetics, bioethics, adoption psychology, law, pediatrics, and other stakeholders in the adoption community that have come together to develop best practices related to genomics and adoption. They are working to develop guidelines surrounding the types of genetic tests and the most appropriate age for such testing to occur for adoptees. Their goal is to provide a set of best practices that will allow adoptees to fill in the gaps in their family health history without the unnecessary stress of potential false positive genetic testing results.

To hear Dr. May talk about this work and other issues that arise surrounding genetic testing, listen to Season 3, Episode 2 of Tiny Expeditions podcast here.